Projects

Team Innsbruck:

Barbara Hausmair (PI, Historical Archaeology)

Ulrike Töchterle (Conservation and Traceology)

Peter Tropper (Geochemistry and Archaeometallurgy)

Cooperation partners:

Mauthausen Memorial (Yvonne Burger & Ralf Lechner)

Lern- und Gedenkort Schloss Hartheim (Florian Schwanninger, Simone Loistl & Peter Eigelsberger)

Prisoner tags from Nazi concentration camps

“To be dispossessed of one’s own name is among the most far-reaching and profound mutilations of the self. It documents the termination of one’s previous life history. … The number signified the metamorphosis of the individual into an element of the mass, the transformation of personal society into the serial society of the nameless.” (Sofsky 1997, 84)

In Nazi concentration camps, one of the most fundamental attacks on victims’ identities and personhood was the replacement of a person’s name with a number. The numbering procedure was part of registration in all concentration camps and one to which deportees were subjected after often days-long, catastrophic transports. In many survivors’ memories registration is recalled as a harrowing act of identity destruction and a fundamental denial of one’s humanity. Prisoner numbers played a crucial role in the administration of KZs. The numbers were typically sewn onto prisoners’ clothes, or in the extreme case of Auschwitz tattooed onto victims’ skin.

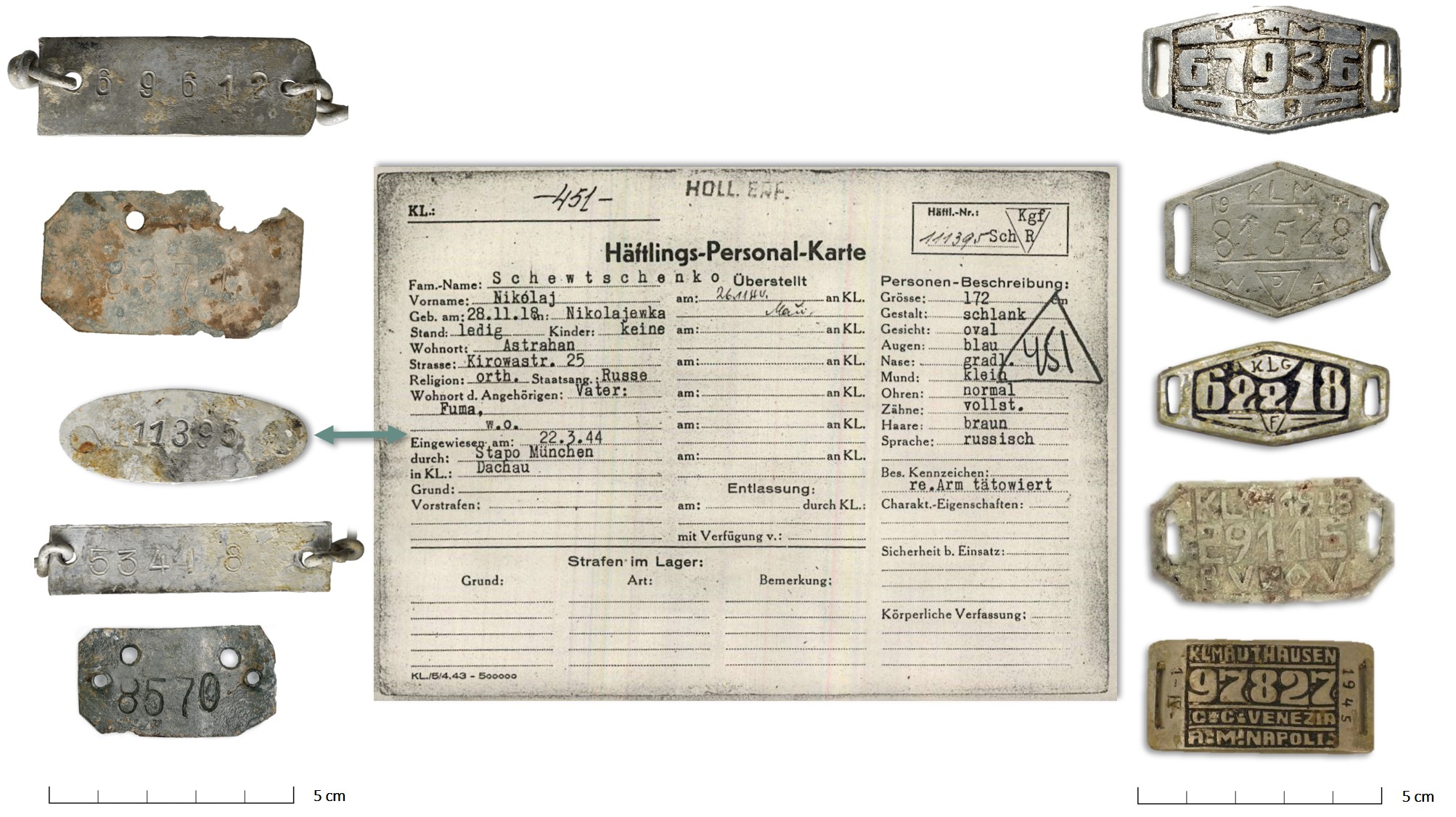

Fig. 1 Prisoner tags from the Mauthausen concentration camp, issued by the SS (left) and crafted by prisoners (right) (Y. Burger/MM; U. Töchterle, Ch. Moritz & I. Thaler/UIBK). Most of the tags can be linked to Mauthausen victims through the preserved prisoner files (centre) (Arolsen Archives, DocID: 1744828).

However, no known SS records explain why in some concentration camps the numbers were additionally issued on metal tags. Yet, preserved artefacts from various camps (Fig. 1), post-war exhumation records (Fig. 2) and – though very few – survivors’ testimonies attest to their existence, pointing to a role as additional means to control the inmates. Among the currently known metal tags, however, there is also a significant number of items that were clearly handmade by prisoners, displaying iconography such as dates, initials or decorations that suggests that these objects were important assets for self-assertion and resistance against dehumanisation.

Fig. 2 A forensic sheet from the post-war exhumation of Mauthausen camp cemetery in the 1950s shows a pre-printed field for tags incl. a rough sketch of a decorated item (OÖLA, 02.06.03, Ordner 2 /351-700).

This research builds on an ethnographic study of M. Schütz (2013) and historical-archaeological pilot-study of prisoner tags from the Mauthausen concentration camp by B. Hausmair (2018). It seeks to comprehensively explore the materiality of dehumanisation but also resistance in Nazi camps by studying the tags, their object biographies, their change of meaning during different stages of Nazi rule and in different camps, and their transformation into objects of identification and memory since the end of the Nazi regime.

Fig. 3 Screenshot of the project database with information on a Mauthausen tag discovered at the Nazi euthanisia site Hartheim castle. That tag carries the prisoner number of Boško Vasić from Ygoslavia and proves that he was murdered in Hartheim (B. Hausmair/UIBK).

The existing project database (Fig. 3) was set up by the project PI in recent years and combines data on artefacts, biographical information on identified prisoners and other relevant archival sources. It currently contains over 1300 records of prisoner tags. Through this fundamental research and data collection, the use of prisoner tags in several concentration camps could be proven. To date, tags are known from the following camps:

Auschwitz

Buchenwald

Dachau / Allach

Flossenbürg

Groß-Rosen

Majdanek

Mauthausen

Neuengamme

Sachsenhausen

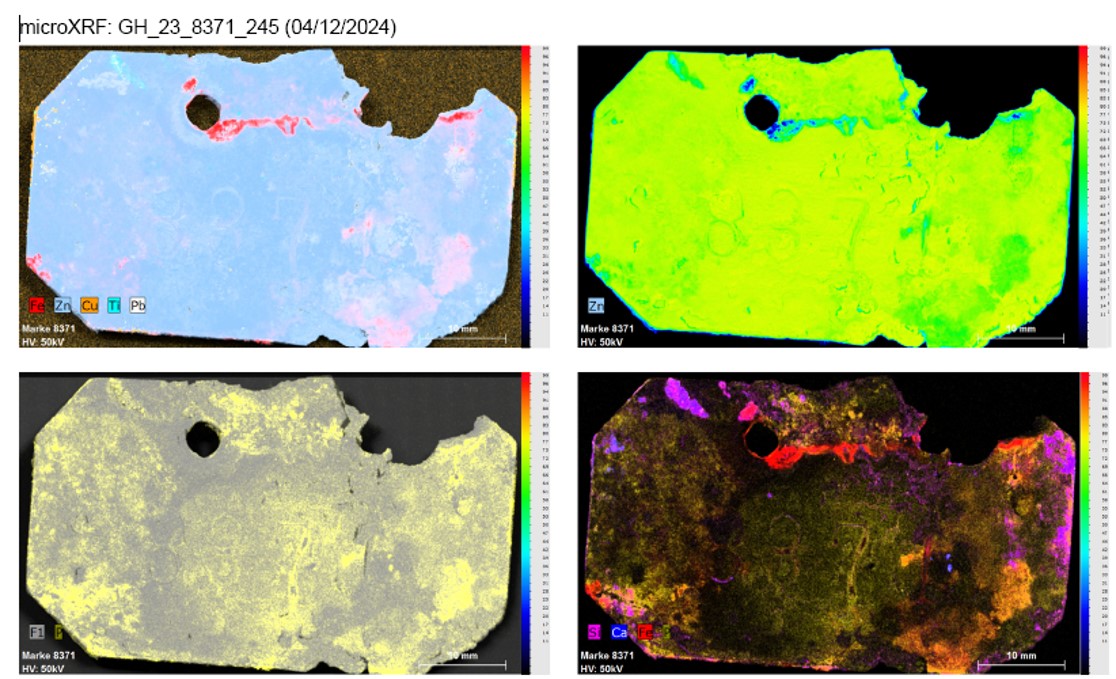

Fig. 4: Elemental analyses such as micro-X-ray Fluorescence allow to determine the material composition of the tags (image: P. Tropper/UIBK).

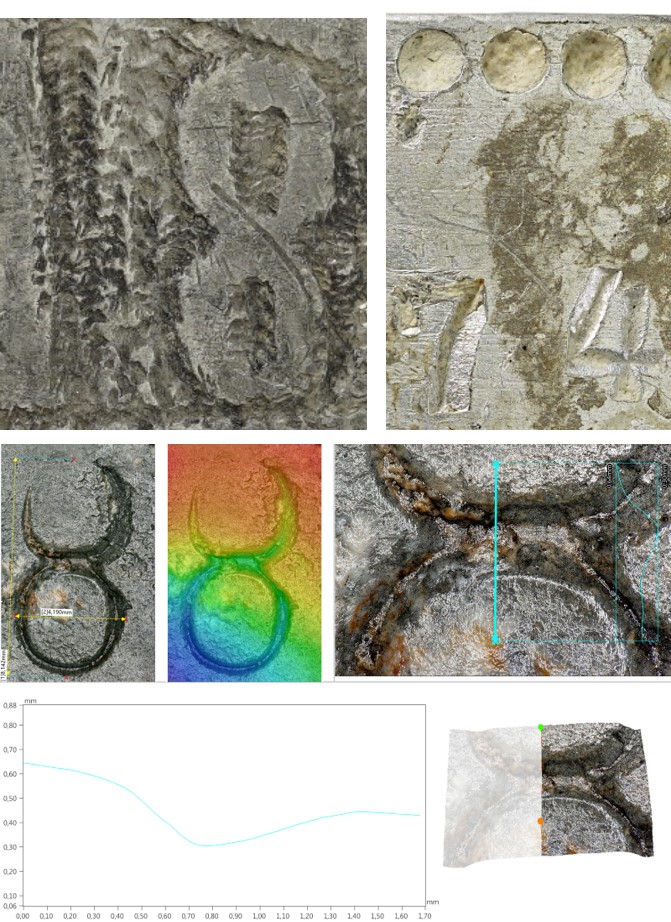

Fig. 5: Macro-photography and digital microscopy enable detailed analyses of production marks and traces of use-wear (photos: U. Töchterle & Ch. Moritz/UIBK).

Coupled with comparisons of tags from other camps, further archival research and evaluation of oral history interviews, the planned project aims to expand our knowledge of this ambivalent group of artefacts within the KZ-system and thus to contribute to the memory of the victims of the Nazi regime (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6: Survivors of camp Ebensee, a sub-camp of Mauthausen, the day after liberation. Joachim Friedner, a Jewish survivor from Poland, is holding his tag into the camera (photo: Arnold Samuelson, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, 111-SC-204480 (Album 3218)).

Acknowledgements

In the course of this research, many concentration camp memorials as well as archives and museums dedicated to the memory of the victims of National Socialism have granted access to their collections, archival materials and knowledge. Photos of prisoner tags from private family collections and/or information about prisoner tags and the biographies of associated inmates were sent to us by committed individuals or relatives of people who were imprisoned by the Nazis. These insights are invaluable to the project and we thank all those who are supporting our endeavours.

Kontakt: barbara.hausmair@uibk.ac.at

Related teaching

- Curating Mauthausen: Objects in the collection of the Mauthausen Memorial (MA seminar and practical, University of Innsbruck, teacher: Barbara Hausmair and Yvonne Burger, summer semester 2023, LVNo: 644160)

- Archaeologies of Nazi Terror (MA lecture, University of Innsbruck, teacher: Barbara Hausmair, summer semester 2022, LVNo: 644160)

- Archaeology of the World Wars (BA/MA seminar, University of Tübingen, teacher: Barbara Hausmair, winter semester 2019/20)

Literature

Burger, Yvonne. 2019. Das vergessene Lager: das ehemalige Waldlager Gunskirchen. MA-Arbeit., Wien: Universität Wien.

Hausmair, Barbara. 2016. ‘Jenseits des „Sichtbarmachens“. Überlegungen zur Relevanz materieller Kultur für die Erforschung nationalsozialistischer Lager am Beispiel Mauthausen’. In Archäologie und Gedächtnis. NS-Lagerstandorte: Erforschen – Bewahren – Vermitteln, hg. von Thomas Kersting, Claudia Theune, Axel Drieschner, and Astrid Ley, 31–45. Denkmalpflege in Berlin und Brandenburg Arbeitsheft 4. Petersberg: Imhof Verlag.

———. 2018. ‘Identity Destruction or Survival in Small Things? Rethinking Prisoner Tags from the Mauthausen Concentration Camp’. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 22 (3): 472–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-017-0436-z

———. 2024. ‘Camp Archaeology in Germany and Austria. A Prospective Review’. In Archäologie und Krieg, hg. von Svend Hansen und Christian Jansen, 35–55. Kolloquien zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte 28. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz-Verlag.

Klimesch, Wolfgang. 2002. ‘Veritatem dies aperit. Vernichtet – Vergraben – Vergessen. Archäologische Spurensuche im Schloss Hartheim’. Jahrbuch des Oberösterreichischen Musealvereins 147 (1): 411–34.

Loistl, Simone, und Florian Schwanninger. 2018. ‘Vestiges and Witnesses: Archaeological Finds from the Nazi Euthanasia Institution of Hartheim as Objects of Research and Education’. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 22 (3): 614–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-017-0441-2

Schütze, Marlene.2013. Löffel, Zigarettenetui, Erkennungsmarke – Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Analyse von Dingen aus dem Konzentrationslager Mauthausen. Univ. Dipl., Wien: Universität Wien.

Sofsky, Wolfgang. 1993. Die Ordnung des Terrors: Das Konzentrationslager. Frankfurt a. Main: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag.

Valley, Émile und Amicale de Mauthausen. 1950. Mauthausen: Plus jamais ça. Paris: Amicale de Mauthausen.